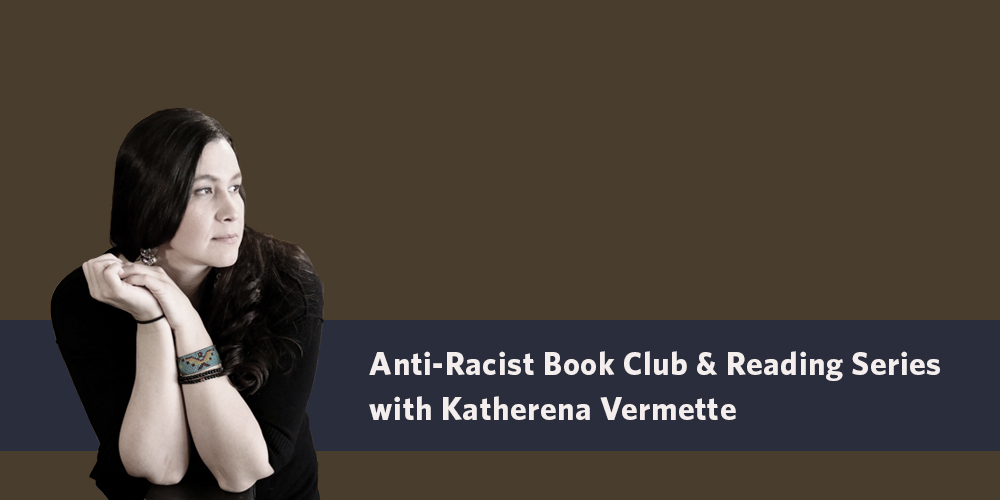

Katherena Vermette. Photo credit: Vanda Fleury

The UBCO anti-racist book club is proud to host an artist talk with Katherena Vermette. On March 23rd, 2022, Vermette will discuss her most recent novel, The Strangers, publicly via zoom. Before the talk, Larissa Piva had the pleasure of sitting down with Katherena for an interview on her book and practice in general.

Larissa Piva is a graduate student in the MFA program with a specialization in Creative Writing. She is working as an academic assistant with Kevin Chong on the Anti-Racist Book Club and Reading Series.

WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO WRITE THIS STORY?

The idea for The Strangers initially was a continuation of The Break, a further exploration of why and how Phoenix came to be the way she is; she was a train that I just had to follow. I also wanted to tell a family story, one that interlaced voices and braided family narrative while traversing generations. The story became this unfolding that I played with quite a bit. One of the really surprising things that surfaced from exploring their voices and lives was this idea of bodily choice. If you’re going to tell the story about family, talking about the person’s choices that brought the people into that family is an interesting thought. It became an obvious connection.

I was familiar with politics around pregnancy choice before, but I did some further research for the novel. I was unfortunately very much familiar with the body politics of Indigenous women specifically and their historical denial of choice. That became one of the main layers. The story unexpectedly became about institutions. Writing it that way came naturally but in editing, I then realized how horrifying the state’s imposition onto Indigenous families is and how so very few of us are unmarked from that heavy surveillance. The criticism and critiques of our ability to parent in our families also surprised me, so I did more research on prisons and the foster care system and followed it. I wanted to specifically explore the intersectionality between Indigenous and female. There are a lot of ideas around family, a lot of ideas around pregnancy and choice, bodily choice, which is not exclusive to women, but in this case, in this story it was important, and I really wanted to talk about those experiences.

YOU MENTIONED THAT FAMILY IS IMPORTANT TO YOU AND INSPIRES YOUR WORK. WHAT POWER OR VALUE DOES FICTION BRING TO PIECES OF ART LIKE THIS THAT NONFICTION JUST CAN’T BRING?

It all has value, but I love working in fiction specifically because you can change what you need to change. Everything is malleable and you can sculpt whatever is needed in a way you cannot do with factual evidence. Whenever I write in the “real world,” I of course still must adhere to certain rules. Timestamps, places. People can’t grow wings and walk on air. But it’s different because I can really make sure you know what I want you to know. I also can introduce more voices and characters into fiction.

WHICH CHAPTER WAS THE MOST DIFFICULT TO WRITE, EMOTIONALLY OR OTHERWISE? WHICH CHARACTER?

The first chapter of Phoenix was probably the most emotionally difficult. It was also the first chapter I wrote. The Break came together in layers, it was all over the place but again Phoenix was that train I had to follow. I wrote that first chapter quickly and I just cried; there was so much pain. It’s an abrupt way to start a book and credit to my editors for not trying to sway me from the artistic choice to start the book like that. Actually, one of the novel’s big criticisms is how Phoenix opens the book: aggressively with a big potty mouth.

She swears a lot, but I do think it is a very white-centric idea, I would venture to say a white upper-class privileged idea, to think that we are all supposed to act and speak a certain way. I am always fascinated by voice. I am fascinated by the way people choose to communicate. So often we learn to communicate in ways that we completely normalize but other groups might not understand, which is why code-switching exists. Swearing and communicating aggressively is Phoenix’s entire world. She fronts this hyper aggression to keep herself safe; that’s what life taught her over and over again. The way she speaks doesn’t negate the value of her experience. I resent the idea that you’re supposed to create this palatable character and spoon-feed them to the masses. No, we have to meet characters, as fictionalized as they are, where they’re at. I want to hear her story through her words, which is a hell of a lot more valuable than any fabricated saturation of couth. My characters have harsh lives so sometimes they have harsh language, harsh ways of presenting themselves. I love them like that, and I wanted to present them like that, not a polished version.

DID YOU BEGIN WRITING THE STRANGERS PRE OR POST-COVID? IF BEFORE, HOW DID YOU FEEL ABOUT MAKING THE CHANGES?

I wrote each character completely before Covid. I had a lot of the book’s bones before it happened, but while weaving the stories together suddenly the world became different. I could have ignored it, just skipped over it to maintain the escapism, but I felt that would’ve fucked up the timeline. That, and writing life events into stories may not seem important now, we think no one will notice, but twenty years down the line, people will definitely notice.

Covid became a hindrance to the characters too. For a lot of the book, Elsie is trying to get together with Cedar and Cedar is trying to get together with Phoenix. It became part of that, another barrier, another hurdle they had to go over. Plastic barriers and masks and social distancing still kept them apart in a lot of ways.

THE CREDITS MENTION HOW YOU TAKE THE NAMES OF YOUR CHARACTERS FROM YOUR FAMILY TREE. YOU MENTION NOT WRITING ANY SPECIFIC FAMILY MEMBERS INTO YOUR NOVELS, BUT HOW DOES IT FEEL TO BRING NEW LIFE INTO A NAME OF A PERSON WHO MAY HAVE LONG PASSED?

I love that idea of bringing new life into the names because I’ve explored these names for so many years. As Michif people, we have extensive genealogies. The church documented us well, they kept track of us in order to contain us, but we’ve used those extensive genealogies to create and maintain community and nationhood, which I love. I love the power of reclaiming that tool but also what it left us: so many names.

Angélique Laliberté is my third great-grandmother I believe. She lived for a long, beautiful time through the 1800s and the Métis world changed threequel in her lifetime. I love her name. Not only Angélique but Laliberté. That means liberty, freedom.

Métis nationhood has a lot to do with those ideas, but that’s almost all I know of her, so I loved bringing her into this other character. Something Métis people do often is name children after those who came before. That’s why we have so many Josephs. We really do! Not only because St. Joseph is our patron saint, but because many people were named Joseph and then they named their children after someone. So, it’s Joseph, Joseph, Joseph. I have lots of Josephs to take from. I kind of made that a joke in my writing because I think every book has a character named Joseph.

*laughs*

You can’t get away from it! I am a total name nerd. Whenever I write, I think about the creation of these big stories around names. I love where they come from and what they mean.

Katherena’s next book, The Circle, is set to be released Fall of 2023. She gave Larissa a few details to share. While each novel stands alone, The Circle is connected to and will include characters from both The Break and The Strangers in an “impetus conclusion.” The novel starts with Phoenix’s release from prison and continues with characters convening.

About the author

Katherena, a Red River Métis (Michif) writer from Treaty 1 territory, is an award-winning author, poet, and filmmaker. To name a few accolades, Vermette’s 2013 poetry collection North End Love Songs received the Governor General’s Award, The Break won the Amazon Canada First Novel Award, and The Strangers received the 2021 Atwood Gibson Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize. When she is not writing, Katherena explores her love for genealogy, supports marginalized youth, and spends time with her family.