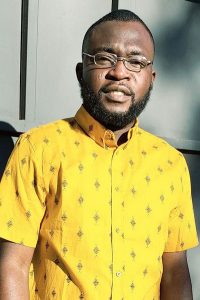

The Faculty of Creative and Critical Studies is pleased to welcome Sakiru Adebayo as the newest member of the Department of English and Cultural Studies. Born in a small town in Southwestern Nigeria, Sakiru moved to Ibadan to study at the University for Ibadan, Nigeria’s premier university. He later moved to Johannesburg, South Africa for his Ph.D. at the University of the Witwatersrand. He worked as a postdoctoral fellow at the Wits Institute of Social and Economic Research (WISER) for a year.

The Faculty of Creative and Critical Studies is pleased to welcome Sakiru Adebayo as the newest member of the Department of English and Cultural Studies. Born in a small town in Southwestern Nigeria, Sakiru moved to Ibadan to study at the University for Ibadan, Nigeria’s premier university. He later moved to Johannesburg, South Africa for his Ph.D. at the University of the Witwatersrand. He worked as a postdoctoral fellow at the Wits Institute of Social and Economic Research (WISER) for a year.

Dr. Adebayo’s research is in the area of African and African diaspora literature, postcolonial studies, and trauma and memory studies. He will be teaching English courses in African and African Diaspora Literature in the coming year.

“I come from a very large Yoruba family in Southwestern Nigeria. My grandmother is the greatest storyteller I know. My fascination with fiction began with the moonlight stories she used to tell us when we were young. It was also partly why I went to study literature at university.”

We met up with Dr. Adebayo to find out a bit more about him, his research and his teaching practices.

Why did you choose to come to UBC Okanagan?

It is very important for me to work in a space that is progressive and to be among people who are genuinely kind and collegial. I think the Department of English and Cultural Studies at UBCO has all of that and more. When you are job hunting, you tend to apply for everything and anything. But that was not my story. I was very intentional about where to and where not to send applications. When I saw UBCO’s job call, I was fully persuaded that the position was written for me (even though I did not know anyone in the Department at that time). I thought my training and expertise in African and African diasporic literatures would be a welcome addition to the already impressive teaching and research portfolio of the Department. In addition, I chose UBCO because I assumed that living in Okanagan will provide me the opportunity to learn more about Canada’s history, especially with regards to the lives, languages and systems of knowledge of its indigenous people. Finally, because I was born and raised in a small town, I kind of prefer a small university town life.

Tell us about your teaching philosophy.

Teaching, for me, has never been an afterthought or a Plan B. I have always wanted to teach for as long as I can remember. Teaching is fun and should always be intentional. My philosophy of teaching is that all students are unique and must be given a stimulating intellectual space where they can grow physically, mentally, emotionally, and socially. I am always very intentional about creating this kind of atmosphere for my students so that they may meet their full potential. Teaching, for me, is also an unending process of learning from my students, colleagues as well as the intellectual community I find myself. This lifelong process of learning new strategies, new ideas, and new philosophies is what I hope to bring to the UBCO. I believe I owe it to my students, as well as the community, to bring consistency, diligence, and warmth to my job in the hope that I can ultimately inspire and encourage such traits in my students as well. I believe the teacher’s role is to act as a guide; therefore, I am not one of those teachers who foist their ideas on their students. Rather, I let students be driven by their impulses, I create an atmosphere where they are able to have choices and let their curiosity direct their learning. This is why my classes are always interactive and participatory. I think this style is particularly necessary for every literature class because, from my experience, not making the texts interactive will bore students and eventually stifle creativity. My goal is to always ensure that my students are actively involved in knowledge making within and outside the classroom. I do all of this with an awareness that the best curriculum is usually the one which incorporates different learning styles with a content that is relevant to students’ lives.

How did you know you wanted to be a professor?

I had this vague obsession with professor Wole Soyinka (the first black and African person to win the Nobel Prize in Literature) when I was very young. I wanted to master the English language the way he did –and, yes, people used to tease me by calling me “the Wole Soyinka of our time”. One of the reasons I went to the University of Ibadan to study English was because Soyinka was, at some point, a student in the same Department (Chinua Achebe was a student there too). However, it was in my third year that things started to become clear to me. That was when we were introduced to literary theory and criticism which completely blew my mind. I was enthralled by the ability to understand the world through different theoretical lenses and to read anything as a text. That was when it dawned on me that being a professor is my calling. I just felt so enraptured by the thought of creating, receiving and imparting knowledge for the rest of my life. Many of my lecturers also encouraged me to enroll for a graduate degree because they thought I had an inquisitive mind and a critical thinking skill. I have neither looked back nor considered any other career since then.

Tell us about your research.

My research is situated broadly in the field of postcolonial studies, but specifically in African and African diaspora literature. I am interested in memory, trauma and melancholy studies in African and African diaspora literature and culture. I have published a few academic papers that address some of these questions. And I am currently finishing a manuscript that is titled, Frictions of Memory in the Postcolony. The manuscript basically looks at how fiction represents –or sometimes causes–memory frictions in post-conflict situations in the postcolony. I am already thinking of a second book project on the new African diaspora. I am interested in the stories of African immigrants in North America especially. What does home mean to them? How do they deal with hyphenated identities and how do they mix or switch cultural codes? I am also trying to think about what it means to immigrate into a country’s past. For example, as I migrate to Canada, what kind of relationship do I have with Canada’s historical injustice toward indigenous communities? Do I bear any responsibility for some of the violence meted out on the indigenous populace? These are some questions I am starting to think of as a research interest.

What most excites you about your field of work?

What I love most about my field is the ability to inhabit stories. Human beings are storied beings and as a literary scholar, I am constantly encountering different stories which help me to understand the world better. Literature allows me to imagine other people’s world and, as a result, become more empathetic toward an/Other. What also excites me about my field is that it is not formulaic, it gives you the freedom to think outside the box. Literature gives room for interdisciplinary thinking, so I can drive my train of thoughts to whichever direction I want. There is something incredibly liberating about that. Also, literature is basically a field of words and sentences. And, you know, a well-written sentence is like music to the soul; a well-punctuated sentence is all it takes for you to have a great day. Being in literature means that I am– more than others– constantly coming across well-structured phrases and deliciously cooked sentences.