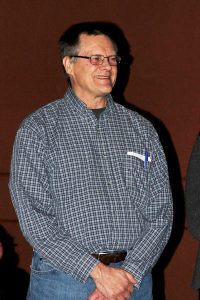

Mihai Covaser in his podcast studio

Mihai Covaser has worked for a number of years with a variety of Canadian organizations related to inclusion and accessibility for youths with disabilities. In the summer of 2021, he received a grant through the #RisingYouth Initiative, presented by the not-for-profit group Every Canadian Counts, to promote social change in his local community.

With this grant, Covaser started a podcast talking to people about the limitations in public schools for people with varying disabilities. Covaser has cerebral palsy, and with this project, his goal is to raise awareness on how schools can be more inclusive and accessible to people with disabilities, using his own lived experience as the basis.

The podcast, entitled Help Teach, brings forward the lived experiences of interviewees, concrete action items for educators, and additional resources in hopes of supporting teachers in their efforts to make their classes more accessible.

Covaser is currently a second-year student working on his Bachelor of Arts degree with a double major in French and Economics, Political Science and Philosophy. In his first year, he took a Digital Humanities (DIHU 220) course that was based around digital audio media and podcasting.

“In that class, we did a podcasting assignment, and after seeing this grant opportunity, I decided, ‘Why not run a podcast on my own’?”

He was able to use the grant money to purchase professional equipment and support for recording, editing, and production. Then in a third year Communications and Rhetoric course (CORH 321), Covaser decided to continue to produce his podcast and use that as his final project, which was to be centered around community service learning.

He explains that the podcast is a collaboration between the grant, the initial project idea, and the class expectations that ended up being really beneficial for him.

“I am able to use skills from the class that I was learning and implement them in the project.” He adds that the podcast is interview based. “My stories and the stories of my interviewees are sort of the evidence and the lived experience that comes forward to drive home the messages.”

Covaser says that the communication and rhetoric class was very interesting to him, being about interpersonal communication and professional and personal identity. The focus was about how we communicate with others, the tools we use to communicate, and how that influences the comprehension of the information that ultimately gets out to people.

“Being part of the class gave me a really unique opportunity to explore a variety of media. It helped me to solidify my choices in the podcast, giving me an opportunity to use my voice exclusively, showing how we can be conscious of the experiences of others when we are communicating.”

He points out that the difficult part about advocating for change like this is that many people work from the bottom up, with individual teachers or students making changes in the classroom for inclusivity. While that may trickle out to other classrooms, his ultimate vision is to work from the top down.

“My ultimate vision is to get the curriculum of educators changed to include more information about accessibility and a variety of disabilities so that teachers come into the classroom already more prepared to accommodate a variety of disabilities.”

The podcast aims to have a variety of perspectives come together to identify the obstacles or the challenges that are most present, and most problematic, and then provide ways of working together towards some solutions. The pilot episodes of Help Teach featured youth leaders from the Rick Hansen Foundation, with whom Covaser works closely to produce this project and others

In an episode released this October, Covaser spoke with a specialist educator, who works with gifted students and students with emotional, mental, and academic challenges.

“Our discussion was fantastic. She talks about being authentic and being intentional.”

He adds that if he could leave one message about this podcast, it would be for educators to think about how they’re being authentic, and how they’re being intentional in their approach to inclusiveness.

Each episode of the podcast ends with a “key takeaway”, which is a concrete action item that an educator could implement in the classroom immediately to help make it more accessible and inclusive for people that may be facing a variety of obstacles to their educational journey.

So far, Covaser has released 10 episodes, with his intended audience being educators in Canadian primary and secondary schools. The education system is under provincial jurisdiction so he has focused the first episodes on his experience in BC, but says he is hoping to generate tools that are useful to all educators.

Listen to the “Help Teach” Podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts and Transistor.